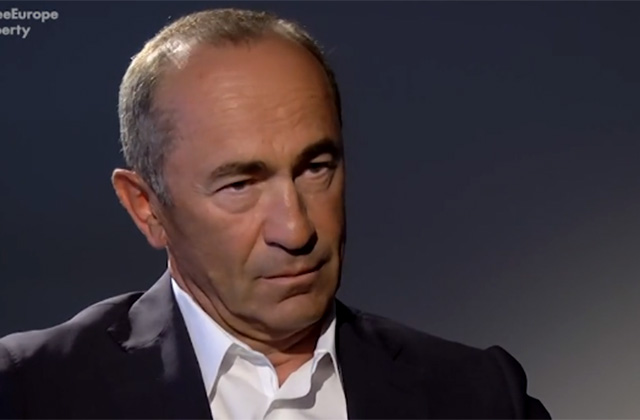

”Russia is more for me than just a country”. Robert Kocharian

Robert Kocharian, president of Armenia (1998-2008)

Anna Sous, RFE/RL Date of interview: September 2015

(This interview was conducted in Russian.)

Anna Sous: What is your Russia like? What does Russia represent to the second president of independent Armenia and the first president of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic?

Robert Kocharian: I had a Russian education. I was brought up in a kind of a mixture of Armenian traditions and Russian culture, art, and literature. So, Russia is more for me than just a country, a neighboring country with which we have extensive relations. Russia for me is associated primarily with its literature and art. I like Russia.

Anna Sous: During your presidency Armenia joined the Council of Europe and the World Trade Organization. You said that in the long run you see Armenia as a country built on European values and according to European principles of government. At the same time, Russia became the leading investor in Armenia. Russian companies own large enterprises in Armenia’s energy, financial, defense, and insurance sectors. There are no “ifs” in history, but if you had a chance, what would you have changed in relations with Russia? I am talking about Russia-Armenia agreements on economic issues. For example, would you change the ownership of Electric Networks of Armenia, or the price of gas? You did recently call for renegotiation of natural gas prices.

Robert Kocharian: The first wave of privatization in Armenia offered the most attractive assets. It was Armenian Telecom, the [Yerevan] Airport concession, Kajaran [Zangezur] Copper and Molybdenum Combine, Hotel Armenia, and the Yerevan Brandy Company. Not one of those was bought by a Russian company, not one. The brandy factory was purchased by French [investors], Telecom by Greek, the Airport by Argentinians, Hotel Armenia by Americans. What else is there? So, that was the first wave. There were no Russian companies. HSBC bank entered the Armenian market way before any Russian bank did.

There were no special preferences for anyone to enter the Armenian market. It was all business oriented. The companies were sold to those foreign investors who made the best offers and had the best development prospects. That’s it. Russian companies’ interest in the energy sector appeared later. Some sort of appetite [grew]. It was me who dragged in Gazprom to set up a joint-venture using agreements reached with the Russian President, etc.

The assumption that Russian companies were eager to enter the market and take it over does not reflect the reality. Electric Networks of Armenia was purchased, privatized by a British company, not a Russian one. This is despite the fact that I had tried to convince RAO UES [the Russian power grid monopoly] to participate in privatization. They said that the market volume was uninteresting. Two years later, they bought it from the British for two times more money. It was when Russian companies saw some future in the energy sector. Although looking at the terms of return on investment, I don’t think any Western company would have agreed to enter our energy sector on these terms. The market volume is not so big, there is no transit component. So, at least for us, only business logic was at work here.

Anna Sous: There are calls for nationalization of Electric Networks of Armenia How realistic is this?

Robert Kocharian: When the company was owned by the state, it was the weakest link in Armenian energy sector. We made a huge effort to find partners, who would buy it – certainly, on specific terms – so we could help our partners bring some order to the company and create a properly functioning utility.

As of 2002, the company worked with a profit and it had stable tariffs up until 2009. Yes, driven by emotions, people are ready to blame anyone when tariffs change, when the price of gas changes. But I believe there is some lack of understanding of the real situation within the energy sector and the company itself. This issue became acute in connection to the general state of the Armenian economy.

If the overall situation is not terribly good, then, naturally, even a small hike in energy prices affects citizens’ disposable income. So people complain.

Anna Sous: Armenia is the only country in the region that hosts a Russian military base. What are the benefits for Armenia from hosting Russia’s 102nd military base in Gyumri? And what are the dangers if any?

Robert Kocharian: Let’s look at it differently. Let’s imagine there is no base. What would be the dangers? Given our relations with Turkey…. Our relations are overshadowed by historical issues, the unresolved conflict around Nagorno-Karabakh. Ours is not a region where there are idyllic relations and everyone is always glad to see their neighbors and welcomes everyone … This is a region with a fairly complicated ethnic and religious makeup. I think the presence of the Russian military base here provides, if not stability per se, then at least a sense of stability. But I actually think it does offer stability. It is something that, nonetheless, stabilizes the situation.

Ann Sous: Speaking of negative consequences of having a Russian military base, what do you think of the public unrest after a Russian soldier murdered an Armenian family [in January 2015]? Is this the kind of situation where the nationality of the murderer is irrelevant? And how could this incident affect Russian-Armenian relations?

Robert Kocharian: Indeed this incident got a very emotional response. The crime itself … it’s unimaginable. But I doubt it will have a long-term negative effect on Russian-Armenian relations.

The protests wouldn’t have been so big and wouldn’t have lasted as long if there had been an appropriate and timely response. The public’s demands were just. The crime had nothing to do with military crimes. It was committed outside the base, within the city.

Naturally, Armenian law-enforcement agencies should have stepped in and lead the investigation. In this case, I do not doubt that the outcry would have been smaller. It would have been emotional, but wouldn’t have had any political demands. If we were to analyze the situation around foreign military bases worldwide, such incidents do happen from time to time everywhere. There just should be an appropriate and fast response. And I think it wouldn’t have hurt if the authorities at the time had demanded more respect for Armenian sovereignty.

Anna Sous: The word ‘protest’ has come up in this conversation a few times already. Armenia has a history of well-developed public protests. In 1965 there were the ones related to the semi-centennial of the Armenian Genocide. There were protests related to Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia’s independence. Is there anything specific about protests in Armenia and can they be at least in part anti-Russian?

Robert Kocharian: I would divide those protests into two distinctive groups. Those that are connected to Nagorno-Karabakh are related to some sort of expectations from people as a nation. I would separate them from the protests that are related to the socioeconomic situation, corruption, or different reactions to elections results by winning and losing sides.

If we separate protests into these groups we will see that the protests are very similar to those in the rest of the world. And the motives are also the same. It is the socioeconomic hardship, prices – something gets more expensive, people protest – it’s corruption, etc., etc.

So I don’t see anything specifically Armenian in this group of protests. Furthermore I don’t see why they would have an antiRussian sentiment. Why should we blame Russia when we talk about economic conditions, policy on tariffs, corruption? As for the first group, that was a part of a national liberation movement. It united all the people whether they like or dislike each other, respect or disrespect, and share or don’t share views on a whole range of different issues. It was a uniting issue.

That wave was completely different and it took place against the backdrop of a disintegrating Soviet Union – geopolitical events of tectonic scale. This sent shock waves across the entire post-Soviet space.

Anna Sous: Has there been any change in the geopolitical context for Nagorno-Karabakh since the annexation of Crimea?

Robert Kocharian: I don’t think anything has changed. There have been a lot of various precedents in past 10 to 15 years. I don’t think the situation around Crimea has added anything new.

Anna Sous: Mr. President, to whom does Crimea belong?

Robert Kocharian: Now? Now, de facto, it’s Russian. And Ukraine, for a long time, will consider it to be part of Ukraine. Russia for a long time … not a long time … Russia has de facto included Crimea into the Russian Federation and I think this will go on for a long time. From our experience with Karabakh, these kinds of situations are never resolved quickly. Years will pass, generations will change. Unless a way to make Crimea a common space for Russia and Ukraine is found.

There are such ideas. I know that some experts suggest the creation of a kind of a condominium which would make a factual attachment of Crimea to either country practically unimportant. Effectively it would create a situation where Ukrainians would be just as comfortable in Crimea [as Russians are]. It’s too early to talk about it. A serious discussion can begin when shots cease to be fired in eastern Ukraine, and when the situation normalizes to the point that such ideas are no longer considered heresy.

Anna Sous: Sergei Nigoyan, a Ukrainian citizen of Armenian dissent was one of the first people who died during the protests on Maidan square [in January 2014]. We have talked previously about the military conflict between Ukraine and Russia that followed. If you were the president of Armenia now, given the events in eastern Ukraine, what would be your policy on ArmeniaRussia relations?

Robert Kocharian: I would like to talk about the period between 1992 and 1994, the acute phase of the conflict around Nagorno-Karabakh. What did Ukraine and Russia do at the time? They were building relations with Azerbaijan and Armenia, while trying to avoid any sensitive issues. This is what Armenia should do.

There will always be conflict. But there is Russia and there is Ukraine, with both we have always had relations. We must continue, but avoid getting into [the conflict], avoid the sensitive issues that can annoy either side. I think this would be the most pragmatic approach for the small country of Armenia, which itself has complicated conflicts to solve.

Anna Sous: Given your experience, your pragmatic approach, what would be your advice to European politicians on how to build relations with Russia?

Robert Kocharian: As far as I can understand, they have put their faith in sanctions. But I don’t believe Russia, given its traditions, its history, its perception of its own identity, the way it sees its role in the world affairs, world culture, world trends, can be pushed to reverse its key decisions. Thus I think finding a system of rewards, rather than punishment, a formula to lure Russia into this process would be more effective. In the case with Russia, it could have had a positive effect.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gBf41YFXqCY&feature=youtu.be