Military-engineering problems and political aspects of collective security

ARTSAKH’S ENERGY SECURITY: POST-WAR CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES[1]

The article considers the main risks and challenges to the energy security of the Republic of Artsakh in the period after the 44-day war in 2020. An analysis of the development of the energy system of Artsakh is carried out to determine its strengths and future potential. The state program for the development of water resources with a focus on the development of hydropower is analyzed. The potential for the development of electricity exports from Artsakh to Armenia in the pre-war period is discussed. The features of the legislative framework for the energy sector of Artsakh are presented, particularly focused on the Law on Energy and the Law on Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency. It is revealed that these laws have great conceptuality and systematic approaches, but they need to be adapted to modern, post-war realities. The main consequences of the 44-day war for the energy sector of Artsakh are studied. The main hydropower plants (HPPs) that passed to Azerbaijan as a result of the war are indicated. The problems of natural gas supplies to Artsakh are considered separately. In particular, the causes and consequences of the accident at the Shushi-Lisagor-Berdzor section in March 2022 are considered. It is established that the long-term paralysis of gas transmission communications in Artsakh should be assessed from the point of view of international law. The author’s maps are presented, reflecting the features of energy infrastructures, as well as the energy potential of Artsakh. It wis revealed that the developed maps can significantly help the authorities of Artsakh in improving the efficiency of energy policy, as well as in developing a new doctrine and a ”road map” to ensure energy security.

Keywords: Artsakh, Nagorno-Karabakh, energy, security, 44-day war, hydropower, gas supply, legislative, energy maps.

Introduction. Energy security is a cornerstone of the Republic of Artsakh’s (Nagorno-Karabakh Republic) economy, given that it is important for powering economic activity, safety and societal development, and enabling human security of its citizens. The 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, also known as the 44-day war, exacerbated and created challenges to achieving energy security in Artsakh. It is reported that the war significantly hindered potential for development of Artsakh and damaged or destroyed energy infrastructure, primarily hydroelectric power plants. Due to the new energy risks and the importance of Artsakh’s energy security for its economy and sovereignty, raising awareness on the current and future state of Artsakh’s energy system is crucial and time sensitive. In addition, the availability of public information of Artsakh’s energy systems is very limited, especially from Armenian institutions and perspectives. Due to the lack of information currently available, this article will aim to uncover the baseline and outlook of Artsakh’s energy security and its relationship with human security.

Research Methodology. The research methodology is based on an integrated approach. First, a thorough literature review of scientific and regulatory literature, news, and media on the current status of Artsakh’s energy sector was conducted. The goal of the literature review was to (i) identify and assess Artsakh’s energy generation and transmission infrastructure before and after the 2020 war, (ii) collect available geospatial data to develop a map with locations of Artsakh’s current energy infrastructure, (iii) collect electricity demand data, and (iv) assess potential for development of renewable energy resources.

Then, analytical, statistical, and comparative typological methods were applied to synthesize the findings and evaluate the future state of Artsakh’s energy system. Due to the interdisciplinary nature of the study, political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal (PESTEL)-analysis was used to identify the state of energy systems in Artsakh. In conclusion, the article synthesized the (i) baseline and future of Artsakh’s energy system, (ii) geospatial map of energy infrastructure to complement the research, and (iii) recommendations made to the Artsakh government on pursuing energy security.

Literature review. The technical, economic, and political angles of energy security in Artsakh have been explored in a few academic papers and studies. While there is some information available on energy security in Artsakh, there are no comprehensive studies on energy security and development in Artsakh. One paper that addresses the key issues of energy security in Artsakh is written by S. Papikyan (2021), which explores the dynamics of energy development in Artsakh from Soviet times to the present day, including energy development challenges in Artsakh after the 44-day war. Two additional interdisciplinary papers by V. Davtyan (2017) (lead author of this article) and M. Hunayan (2016) explore different aspects of the energy development of Artsakh, including natural gas, hydropower, and electric power distribution system. D. Babayan (2019) examines the geopolitical issues around water resources in Artsakh, including hydropower, and is the first of its kind to point attention to the water resources crisis caused by the Karabakh conflict. The problems of developing the water resources of Artsakh in the context of the energy interests of Azerbaijan and Iran are studied in the article by G. Avetikyan (2020). The problems of energy geopolitics in the South Caucasus in the context of the Karabakh conflict are studied by S. Zhiltsov and E. Savicheva (2021).

Scientific novelty. For the first time, the energy security issues of the Republic of Artsakh after the 44-day war in 2020 are comprehensively studied. This article explores the energy sources that Artsakh had before the war and possible solutions to meet the current gap through alternative energy sources. The pre and post war energy resources were presented as maps to complement models and allow people to visualize the scale of the impact of the war on Artsakh’s energy security and development. The article also includes maps and results on the potential of incorporating solar and wind energy to Artsakh’s grid and energy planning.

This article also touches on the connection between energy security and human security. The article presents a new perspective, indicating that there is high correlation between energy security and human security. Recommendations on human rights laws are presented as possible solutions for raising more international awareness and haltering the continuous hostilities. Overall, this article uses an interdisciplinary approach to understand the impacts of the war on Artsakh’s energy system, incorporating economics, political science, ecology, and cartography.

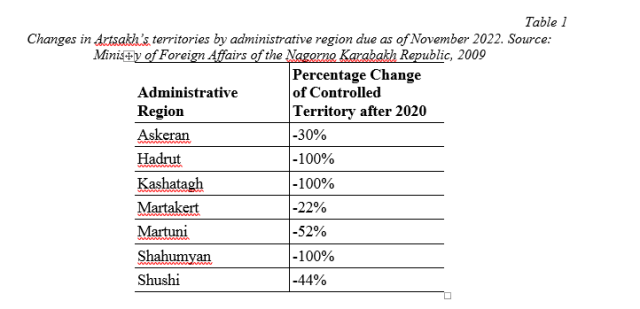

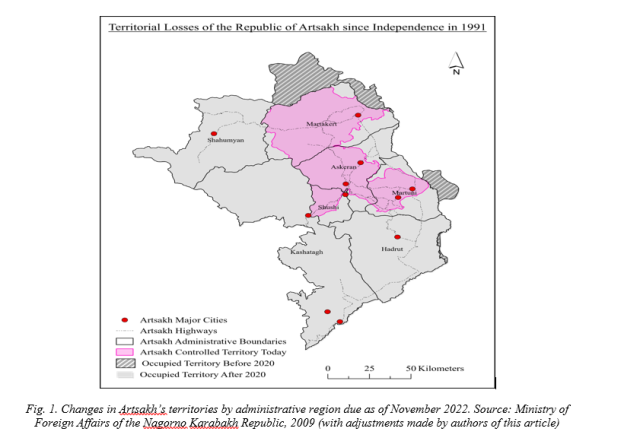

Analysis. Loss of Land. Since the 44-day war, Artsakh has considerably shrunk in size due to land transfer to Azerbaijan. Due to continued conflict, Artsakh continues to lose land, while Azerbaijan gains it. As of November 2022, Azerbaijan has gained three provinces entirely (i.e., Hadrut, Kashatagh, and Shahumyan), in addition to considerable areas of land of the other four provinces (Table 1; Figure 1). The loss of land not only caused loss of energy resources, but also displaced many people and created uncertainty and lack of energy for many in the region, causing a continuous humanitarian crisis.

Electricity transmission. Before the 2020 war, Artsakh’s national energy policy was aimed at modernizing the entire energy infrastructure of Artsakh. As a priority for improving the reliability of the energy system, the transition to a ring power supply scheme was considered, a scheme where two sources of electricity serve the demand of consumers, thus increasing the reliability of the power supply of the system. Electrical installations with a ring power supply are used in urban power networks, mainly in high-voltage underground cable channels for public use. One overhead high-voltage line existed that spanned from Syunik to Kashatagh. The plan was to build a second line, the Arajazor-Karvachar-Zod, which would link Artsakh with Armenia.

The electricity transmission lines connecting Artsakh and Armenia pass through Lachin, which, according to the 3-party statement on the cessation of hostilities of November 10, 2020, was passed to Azerbaijan [President of Russia, 2020]. This circumstance creates serious risks for the energy security of Artsakh and dictates the need to find new ways to connect the power lines from Artsakh to Armenia.

Before the war, the Martuni province of Artsakh was supplied with electricity through the Shushi-Karmir Shuka-Martuni power transmission line. After the war, a significant part of this line fell under the control of Azerbaijan. To solve this problem, a 41 km high-voltage power line (Stepanakert-Martuni) was built, with a capacity of 10 MW. Currently, the Martuni province consumes up to 3 MW. It is important to note that the constructed line will also connect to the Karmir Shuka substation, and 443 support poles have already been built to support these transmission lines. The work was carried out by the “Artsakhenergo” company, and cost about 1.5 billion AMD [Papikyan, p. 57].

Prior to the 2020 war, social justice and equal access was the heart of the energy development plan in Artsakh. Through subsidies, the government of Artsakh sought to ease the financial burden on the population. In 2017 alone, 2.6 billion AMD were allocated from the state budget to subsidize tariffs and make energy more accessible [Papikyan, p. 19]. However, due to the current state of Artsakh and continued conflict, the energy development plan and access to electricity to create social justice and equal access needs to be revisited.

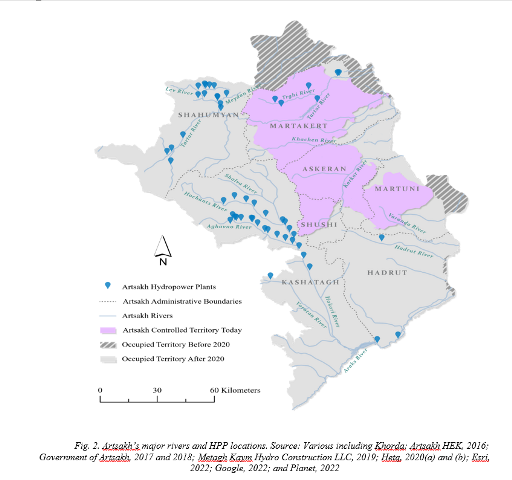

Hydropower energy. Prior to the 2020 war, Artsakh’s energy goals included increasing energy security within its borders and promoting energy independence. Artsakh has an abundance of water resources and had over 30 hydropower plants built and more planned to meet energy needs (Figure 2). The “Water Legislation,” (2007) a basic law for the implementation of state policy, was adopted in Artsakh to regulate and control the water sector. The “Water Legislation” also defines the fundamental principles and rules for the use of water resources. The total potential of Artsakh’s energy before the 2020 war, according to the plans of the “Water Legislation,” made it a possibility to generate up to 700 million kWh of electricity, which was almost twice as much as domestic needs, creating ample opportunities for export and thus economic benefits for Artsakh.

The “Development of the NKR Water Resources” (2008b) is a program under Artsakh’s guiding national policy on hydropower. The goal of the program is to increase the level of national security through the development of the energy security system. The main objectives of the program between 2008-2015 were (i) construction and further operation of new small HPPs on the rivers flowing through the territory of the republic; (ii) technical re-equipment of enterprises involved in the hydropower industry based on the latest technologies; and (iii) attraction of internal and external investments with their direction for the development of the industry.

Within the framework of the program of activities of the Artsakh’s government for 2012-2017, construction of new HPPs were planned, in addition to the currently operation Sarsang HPP, and together the planned and existing dams, would be able to generate up to 400 million kWh of electricity per year [Government of Artsakh, 2008a]. Along with this, the program indicated that in Artsakh, the demand for electricity in the Republic would amount to 300 million kWh. The excess energy export of 100 million kWh could provide Artsakh’s economy with a profit of about 2-2.5 billion dram (AMD) per year.

According to the program, it was deemed necessary to build five small hydropower plants (HPPs) (up to 10 MW) and a cascade of two HPPs on the Tartar River to meet the country’s energy demand and exports. As a result of the implementation of the program, Artsakh was planned to achieve 100% of electricity needs exclusively from water resources, in addition to exporting electricity through development of new transmission corridors.

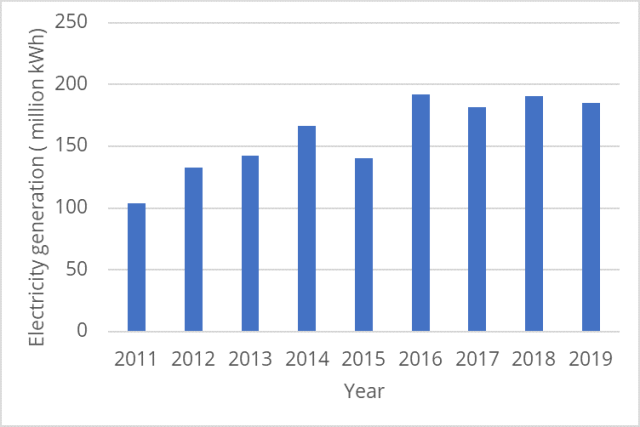

The eight-year program, with the goal of creating an energy surplus in Artsakh, had outlined two major phases. The program included the consideration that between 2005-2010, Artsakh was generating about 40-50% of its energy demand [Armenpress, 2013]. Within the framework of the first stage (2008-2011), five small HPPs with a capacity of up to 10 MW were built on the Tartar River, as well as on the conduit between the Trga and Tartar Rivers. A cascade consisting of two HPPs on Tartar River (near the village of Matagis) were built. Along with this, the program supported the construction of a cascade consisting of three HPPs on the Trgi-Tartar canal. As a result of the completion of the program’s first stage, electricity generation in Artsakh increased to 210-225 million kWh. This allowed Artsakh to save up to 1.5 billion AMD and direct these funds to the development of the hydropower industry. During the second stage (2012-2015), additional HPPs were constructed, which allowed Artsakh to generate up to 350 million kWh of energy [Davtyan, p. 14]. By 2013, Artsakh was able to generate and fulfill 85% of its domestic electricity demand. However, due to the loss of land and HPPs, instead of increasing energy supply and being an exporter, Artsakh currently experiences a deficit.

To implement the program, a significant part of the funding was provided in 2009 by the launch of the Initial Public Offering (IPO) of the state-owned hydropower company, Artsakh HPP. The IPO became a part of the reforms implemented by Artsakh in the energy sector that aimed at increasing the level of energy security and independence [Armenbrok, 2010]. Thus, the population of Artsakh, as well as Armenia and the Armenian Diaspora had the opportunity to directly participate in the formation and development of the energy system of the Artsakh by having the opportunity to invest in the energy sector [Davtyan, p. 15]. In 2019, 184.9 million kWh of electricity was produced by Artsakh HPP (Figure 3), allowing Artsakh to consider energy exports to Armenia [Artsakh Hek, 2019].

Fig. 3. Electricity generation at “Artsakh HPP” from 2011- 2019.

Source: Artsakh Hek

After the 2020 war, only 5 HPPs remain in Artsakh HPP – Sarsang and four HPPs on Trgi cascade. The total capacity of these five HPPs is 79.5 MW. Sarsang HPP has the largest capacity among them (50 MW) [Ibid, 2019]. As a result of the war in 2020, the Mataghis-1 (4.8 MW) and Matagis-2 (3 MW) HPPs, which were part of the ”Artsakh HPP”, were passed into the possession of Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan also occupied the Charhek HPP, Karvachar HPP, Lev-1 HPP, Zangezur HPP, Mrav HPP, among others [Armenpress, 2021].

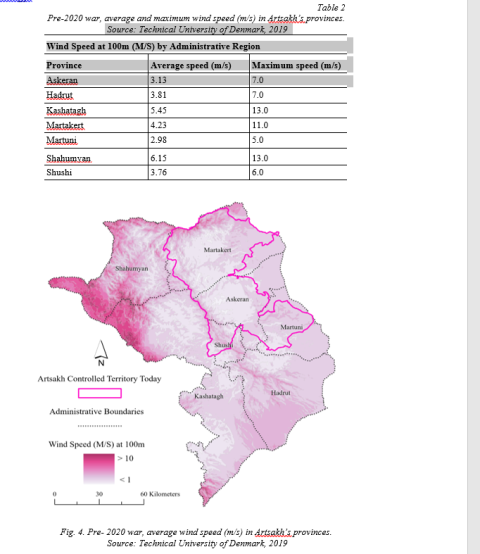

Wind energy. While there are currently no wind turbines producing electricity in Artsakh, limited data is available on the potential of wind energy. Wind speed, along with height of installed wind turbines, is a primary input for estimating potential electricity production, in the former and current boundaries of Artsakh. After the 2020 war, the Azerbaijani government publicized plans to explore the potential of wind energy development in the occupied territories, citing that potential that reaches 2,000 MW [Caspian News, 2022]. The Shahumyan province has the greatest potential for wind energy, followed by Kashatagh and Martakert provinces (Table 2; Figure 4). Unfortunately, Shahumyan and Kashatagh provinces have been completely occupied by Azerbaijan which had the highest wind energy potential for Artsakh. However, there are still some regions in present-day Artsakh that could be prioritized and good candidates for building wind energy.

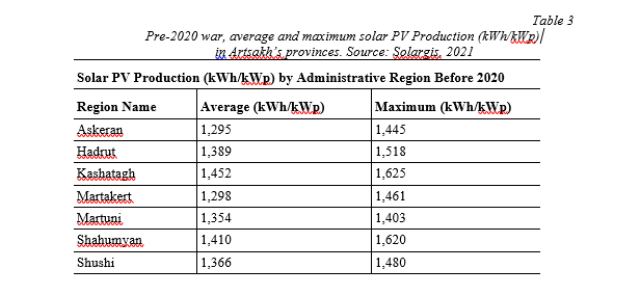

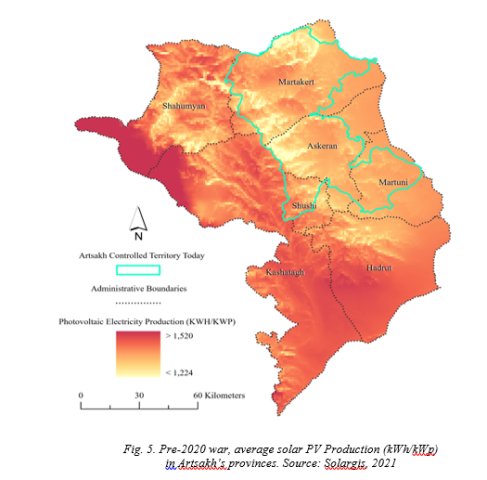

Solar energy. Although there are no utility-scale solar photovoltaic (PV) plants in Artsakh, similar to wind energy, there is considerable potential for using solar energy for heating water and electricity in Artsakh, via solar water heaters and solar PV plants, respectively. Due to its geographic location and elevation, Artsakh has considerable solar resources. For example, data shows that Stepanakert has a global horizontal radiation (GHI) value of 4.04 Kilowatt-hours (kWh)/m2/day per year [NASA, 2005], which is a primary input into estimating solar PV electricity generation. This is higher than in most parts of continental Europe [Solargis, 2021]. The Azerbaijani government has published data claiming that occupied areas in Artsakh have a potential of 2,000 MW [Caspian News, 2022]. This potential has been recognized by Artsakh’s government in the past [Armenpress, 2017] and already utilized by energy companies and non-governmental organizations in solar energy installation projects [Civilnet, 2022]. Kashatagh has the highest solar PV production potential, followed by Shahumyan and Hadrut (Table 3; Figure 5). All three of these provinces have been occupied by Azerbaijan. However, parts of the other four provinces that Artsakh still has partial control of have adequate potential for solar PV production, particularly Shushi and Martuni.

Minerals and other fuels. Before the war, exploration was carried out in Artsakh to determine the presence of minerals. Geological exploration showed that there are some types of solid fuel minerals and coal. The mineral reserves are estimated at up to 15 million tons located at the Magavuz group of deposits, Martakert region [Environmental Protection Committee of the Republic of Artsakh]. In October 2012, the first batch of coal (26 wagons of 60 tons) was delivered to the Yerevan Thermal Power Plant (Yerevan TPP). It was expected that by the end of 2012, up to 700,000 tons of coal would be supplied to thermal power plants, and by 2013, exports from Artsakh would reach 1.5 million tons. However, the exploration of this project was suspended due to two reasons. First, it required a new technology, as the Yerevan TPP has never produced electricity using coal, making this less feasible as an option. Second, there was opposition from civil institutions since the use of coal would increase carbon dioxide emissions, thus contributing to air pollution and climate change.

Geological exploration was also carried out in the villages of Nareshat and Kolatak. Subsoil exploration for liquid and gaseous fuels was conducted in the Martakert-Martuni-Hadrut region, as well as the Hadrut-Kashatah region. Currently, geological exploration stopped due to the transfer of territories to Azerbaijan after the 2020 war.

Energy and the economy. Before the 2020 war, the energy system of Artsakh was a cornerstone of the economy, allowing Artsakh’s development to accelerate. In July 2014, the Russian television channel RBC described Artsakh as a “Transcaucasian tiger,” alluding to its rapid economic growth [Panorama, 2014]. From 2015 up until 2021, Artsakh’s economy was growing (2016: +9.7%, 2017: +18.5%, 2018:+14.0% , 2019: +10.4%), largely due to the construction of energy infrastructure and the growth of energy consumption. In 2020, the economic decline in Artsakh amounted to -20.9%, followed by -7.9% in 2021 [Civilnet, 2022].

Legislative framework for energy development. In Artsakh, a legislative framework that defines the basic principles and directions for the development of the energy industry is crucial. Artsakh has a well-established legislation that highlights the importance of the multi-level dynamics of energy development. The laws regulating the energy industry are distinguished both by their conceptuality and applied value.

There are two important legislative frameworks for energy development in Artsakh: the “NKR Law on Energy” (2002) and the “NKR Law on Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy” (2005). These laws lay the foundations and guiding principles for the long-term development of the energy industry, including strengthening economic and energy independence, increasing the degree of energy security and reliability of the energy system, creating new industries that stimulate energy saving and development of renewable energy, diversifying the energy system and improving energy efficiency, and reducing impacts on the environment and human health. In addition, these laws highlight the importance of protection of the rights and balancing of the interests of energy consumers and energy producers, ensuring the transparency of licensing activities, public administration and regulation, and others.

In the “NKR Law on Energy,” a strong link is made between energy infrastructure and economics. This law focuses on stimulating investment in the energy industry, strengthening energy independence of Artsakh through the diversification of energy resources, maximizing production, supporting scientific and technical activities for energy efficiency and energy conservation, introducing new technologies, and training and retraining of personnel. The “NKR Law on Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy” focuses on the national energy policy with a conceptual vision of the “energy future” of Artsakh. This includes increasing the level of satisfaction of its citizens, the business for energy resources using their own renewable sources, and development and stimulation of the use of new technology. However, taking into account the new risks to Artsakh’s energy security, it is necessary to significantly revise the legislation, adapting it to new realities and challenges. For example, new legislation would consider the loss of HPPs to Azerbaijan, potential for solar energy development, and potential electricity transmission connections to Armenia.

Artsakh’s energy security: Post-war. As a result of the 2020 war, the energy system of Artsakh has become uncertain and has experienced many negative consequences. Today, systematic and large-scale work is required to restore stable energy supplies. As of November 16, 2020, the supply of electricity was suspended in the Martuni region (Chartar, Sos, Machkalashen, Qarahunj, Qert, Kolkhozashen, Kavakhan, Msmna, Kherkhan, Tsovategh, Kherkher, Karmir Shuka, Tagavard, Kaler, Skhtorashen villages) and the Askeran district (Sznek, Mkhitarashen, Khachmach, Karmir Gyugh villages). By November 22, 2020, the supply was restored to Berdashen, Ashan, Norshen, Emishchan, Khatsi, Gishi, Spitakashen, Mushkapat, Khagorti, Kagartsi, and Paraatumb villages [Papikyan, p. 56].

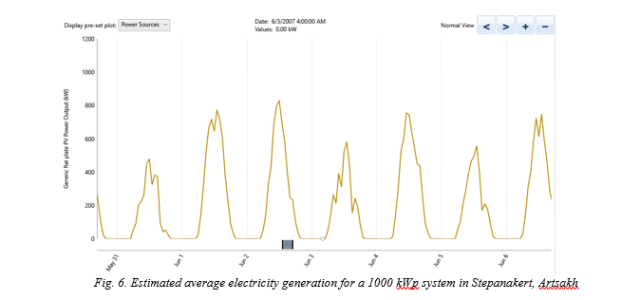

Due to restoration work, the supply of electricity is periodically interrupted and not always reliable. In order to overcome the energy crisis in Artsakh, it is necessary to implement programs for the development of renewable energy. It is estimated that the construction of a 1000 kW solar PV plant will make it possible to produce more than 1.5 billion kWh of electricity annually, while causing less impact to the environment compared to other sources of energy [Papikyan, 2021]. Electricity produced by solar PV significantly displaces electricity otherwise produced by fossil fuels and other resources that have greater life cycle emissions, including combustion and transportation of carbon-intensive fuels transportation [Solar Industries Association, 2022]. It is estimated that the solar power plant can reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 724 tons. In order to build solar energy, capital investments are estimated at 300 million AMD. Modeled in HOMER software, such a solar PV plant using generic solar PV panels installed in Stepanakert would have an average daily output of 3,691 kWh/day (Figure 6).

Since Artsakh will receive natural gas from Armenia, it is expected that the commissioning of such a solar PV plant would reduce demand for electricity production at the Yerevan TPP. At the same time, studies show that when such an amount of gas fuel is burned at the Yerevan TPP, it leads to the emission of greenhouse gasses and other pollutants into the atmosphere, including 2 kg of sulfur and 1,880 kg of nitrogen oxide [Ibid, 2019]. Sulfur and nitrogen oxide contribute to air pollution and acid rain, which is harmful to human health and the natural environment.

The war has also impacted the supply of natural gas in Artsakh. Artsakh has been involved in the natural gas industry for over five decades. In 1960, Stepanakert was a supplier of liquid gas and over the decade developed a larger liquid gas industry. Further, in 1976, Artsakh began large-scale gasification with natural gas. In 1992, due to hostilities with Azerbaijan, gas supply was completely suspended in Artsakh, leaving more than 80% of gas distribution stations in an emergency state. A year later Artsakh resumed supplying gas, but it required a considerable amount of effort to determine which entity within Artsakh would take over responsibility for the gas transportation system. In 1993, according to the decision of the State Committee for Defense, the regional gas production company of Stepanakert was reorganized into the ”Artsakhgaz” production enterprise, which in 1999 received the legal status of a closed joint-stock company (CJSC) with the sole founder being the government of Artsakh [”Artsakhgaz” CJSC, 2022]. The main activities of the “Artsakhgaz” CJSC include (i) import, transmission and distribution of natural gas; (ii) construction of a natural gas transmission network; (iii) construction of a distribution network; (iv) construction of a network of a gas transmission system operator; (v) provision of gas transportation system services; and (v) provision of house maintenance services.

Before the 44-day war, the ”Artsakhgaz” company operated 7 production and operational sites in Stepanakert, Shushi, Martakert, Martuni, Hadrut, Tog, and Khachen, meeting 67.1% of Artsakh’s gas demand (93% of cities and 43.1% of villages). The remainder of the supply was imported from Armenia. In the post-war period, although current gasification data are not available, natural gas tariffs in Artsakh increased as a new rate was negotiated. On average, natural gas tariffs in Armenia were increased by 4.7 drams in April 2022. Due to the increase in tariffs and reliability on Armenia’s supply, additional risks for social stability and accessibility were created after the war.

After the 44-day war, risks and accidents during gas transportation have also increased. On the night of March 8, 2022, due to an accident at the Shushi-Lisagor-Berdzor pipeline in the Shushi region (under the control of Azerbaijan), the gas supply to Artsakh from Armenia was stopped [Armenpress, 2022a]. Azerbaijan hindered the implementation of repair work on the gas pipeline after the accident and in fact the accident was associated with intensive shelling by the Azerbaijani Armed Forces at the Khramort, Parukh and Khnapat settlements of the Askeran region of Artsakh [Hetq, 2022]. Initially, Azerbaijan did not allow Armenia, Artsakh, or Russian peacemaker authorities to approach the gas pipeline to restore it. However, as a result of negotiations with the assistance of the Armenian government and Russian peacekeepers, Azerbaijan restored the damaged pipeline. However, since March 21, due to the intervention of Azerbaijan, gas has not been supplied to Artsakh again. The Artsakh government stated that there is sufficient evidence to prove that Azerbaijan installed a control valve in the pipeline causing the gas supply to stop. As hostilities and land acquisition by Azerbaijan continues, the risk of similar accidents related to energy supply continue to be a serious issue.

Due to suspending the gas supply, Artsakh’s residents’ basic rights have been violated. The European Union was one of the first to react to this violation, expressing concern about the suspension of gas supplies to Artsakh, calling on Azerbaijan to restore supply [Armenpress, 2022b]. The accident in Artsakh in March 2022 can be described as a humanitarian catastrophe, as the lack of gas supplies and problems with the supply of electricity has left the population of Artsakh in an extremely difficult condition, particularly during cold winter months. Since Artsakh is not globally recognized, receiving aid and diplomatic discussions remain particularly difficult. Some international laws such as the Declaration of Social Progress and Development (1969), International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966), Universal Declaration on the Elimination of Hunger and Malnutrition (1973), among others should be considered as avenues for addressing these human rights violations.

Conclusion. Prior to the 44-day war, Artsakh’s development was progressing quickly, particularly due to the economic gains from the energy sector. Artsakh’s loss of land and transfer of land created very difficult challenges to the population, especially for energy and gas supply for its people and the economic ramifications. The challenges for electricity created a new reality for Artsakh’s energy supply, transmission, and policy.

Impacts to energy and gas were severely impacted in Artsakh due to the 44-day war. Due to the land transfer, Artsakh no longer has possession of the major corridor that will allow export to Armenia and has to re-create and design a new system for transmission of electricity. With the ongoing hostilities and continuous land transfer to Azerbaijan, it is becoming increasingly difficult to plan and follow through with new plans for export.

Additionally, the transfer of land has caused Artsakh to change its energy portfolio. Only a few hydropower plants remain in the possession of Artsakh, which was the main source of energy for Artsakh. The loss of these water infrastructure have directly impacted the economy, in addition to the water resources and electricity benefits. The public offering of shares of Artsakh HPP OJSC (IPO) allowed Artsakh to adopt a new system for its financial and economic institutions. Only five Artsakh HPP OJSC remain in Artsakh’s boundaries.

Due to the impacts on hydropower and lost electricity supply, Artsakh has to reinvision its energy portfolio and policy. Adding solar and wind energy into Artsakh’s portfolio is one way to meet the new energy gaps. Both of these sources of renewable energy have great potential given Artsakh’s geographic characteristics. Unfortunately, some of the highest areas of wind and solar energy are now occupied by Azerbaijan. However, given that renewable energy sources are now more reliable and generally economically more feasible than fossil fuel sources, and Artsakh already has sound policies around renewable energy, this could be a reliable source of energy for Artsakh and also can help close the energy gap the war has created.

The problem of natural gas supplies to Artsakh continues to be one of the key ones. The Shushi-Lisagor-Berdzor gas pipeline accident in the Shushi region (under the control of Azerbaijan) in March 2022, prevented the people of Artsakh, Armenia, and Russian peacemakers to access the pipeline, causing gas supply to be suspended, leaving many in Artsakh without gas for a prolonged period of time. This accident and lack of immediate repair was a violation of basic human rights by Azerbaijan. This violation must be assessed within the framework of international law in accordance with international conventions to ensure that such violations do not repeat.

Overall, it is necessary to adapt the legislative framework in the energy sector of Artsakh to the current geopolitical realities in the region. In this framework, it is important to develop and adopt a new energy security doctrine that defines the main external (geopolitical and geo-economic) and internal (technical, personnel, managerial, financial) risks and challenges. Artsakh’s energy security should be based on the principle of deepening energy cooperation with Armenia in order to expand energy trade. The doctrine of Artsakh’s energy security should form the basis of the “road map” for the development of the energy system and the market, the implementation of which should become a government priority. However, the main challenges lie in the development of a new model of energy security with energy self-sufficiency and sustainability.

Energy security and its impacts to Artsakh’s people continue to be detrimental. Armenian diplomats need to most actively raise the issue of violation of the basic, including economic, rights of the people of Artsakh after the 2020 war. In addition, on an international level, the link between energy security and human rights in Artsakh must be raised and the violations must be recognized. Without recognition, Artsakh’s challenges in the energy sector, and thus its direct ties to human rights continue to be violated. Through this article, the summary of the pre and post war reality in Artsakh are outlined, and some solutions and recommendations to address them can be adopted by lawmakers, organizations, and advocates.

References

- Avetikyan, G. 2020 War in Nagorno Karabakh: Regional Dimension // Ways to Peace and Security. – 2020. – No. 2(59). – P. 181-191

- Babayan, D. Hydropolitics of the Azerbaijan-Karabakh Conflict. – Moscow and Yerevan: De Facto Publishing House, 2019. – 152 p.

- Davtyan, V. Development of the Hydro-Energy Complex of Republic of Artsakh // Proceedings of NPUA: Electrical Engineering, Energetics. -2017. – No. 2. – P. 9-21.

- Hunanyan, M. The role of Artsakh HPP in the development of Karabakh energy system // The 25th anniversary of NKR Statehood” international scientific conference proceedings. – Stepanakert, 2016. – P. 292-298.

- Papikyan, S. Artsakh’s Energy. – Yerevan, Institute for Economics (NAS RA), Armenian Academy for Energy, 2021. – 132 p.

- Zhiltsov, S., Savicheva, E. Regional Security in the South Caucasus: The Energy Factor // Post-Soviet Issues. – 2021. – No 8(3). – P. 331-340. (In Russ.).

- United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). (1966). United Nations. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Resolution 2200A (XXI). Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights

- United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). (1969). Declaration on Social Progress and Development. Resolution 2542 (XXIV). Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights

- United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). (1974). Universal Declaration on the Eradication of Hunger and Malnutrition. Resolution 3180 (XXVIII). Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/universal-declaration-eradication-hunger-and-malnutrition

- Government of Artsakh. (2002). NKR Law on Energy.

- Government of Artsakh. (2005). NKR Law on Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy.

- Government of Artsakh. (2007). Water Legislation of NKR. Stepanakert.

- Government of Artsakh. (2008a). Program of activities of the NKR government for 2012-2017. Stepanakert.

- Government of Artsakh. (2008b). Development of Water Resources of the NKR, Government target program. Stepanakert.

- Government of Artsakh. (2017). Decision about issuing licenses. Retrieved from http://arlexis.am/DocumentView.aspx?docid=25534

- Government of Artsakh. (2018). Superintendent Normative Acts Information. https://minjustnkr.am/nkr/documents/08-159.pdf

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Nagorno Karabakh Republic. (2009).De Jure Population by Administrative Territorial Distribution and Density (with map). Census in NKR 2005.

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). (2005). Surface meteorology and Solar Energy (SSE) Data Archive. Retrieved from HOMER; https://asdc.larc.nasa.gov/project/SSE

- President of Russia. (2020). Announcement of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, the Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia and the President of the Russian Federation. Retrieved from http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/64384

- Solar Energy Industries Association. (2022). Climate change. Retrieved from https://www.seia.org/initiatives/climate-change

- (2021). Solar resources maps of Europe. Retrieved from https://solargis.com/maps-and-gis-data/download/europe

- Technical University of Denmark. (2019). Global Wind Atlas 3.0. Retrieved from https://globalwindatlas.info/en

- (2010). Artsakh HEK HydroPowerPlant: Initial Public Offering Investment Memorandum. Retrieved from https://armswissbank.am/upload/Azdagir_AHEK_eng.pdf

- (2013). Artsakh will first export the increased electricity to Armenia. Retrieved from armenpress.am/arm/news/716221/izlishki-elektroenergii-viyrabatiyvaemogo-v-arcakhe-prezhde.html

- (2017). Government of Artsakh develops solar energy branch. Retrieved from https://armenpress.am/eng/news/894978/government-of-artsakh-develops-solar-energy-branch.html

- (2021). The licenses of hydropower plants outside the control of Artsakh have been declared invalid. Retrieved from https://armenpress.am/arm/news/1041860.html

- (2022a). Artsakh gas pipeline repair works to start after demining. Retrieved from https://armenpress.am/eng/news/1077405.html

- (2022b). EU concerned about renewed cuts of gas supply in Artsakh. Retrieved from https://armenpress.am/eng/news/1078660/

- Artsakh HEK. (2016). Artsakh HEK Open Joint-Stock Company. Retrieved from http://artsakhhek.am/?lang=en

- Artsakh Hek. (2019). Strategy. Retrieved from http://artsakhhek.am/?page_id=125

- ”Artsakhgaz” CJSC. (2022). Gas supply. Retrieved from http://artsakhgaz.am/page/119

- Caspian News. (2022). Retrieved from https://caspiannews.com/news-detail/azerbaijans-karabakh-region-to-go-green-2022-5-18-0/

- (2022). In Armenia’s Akunk village, a grassroots push for solar power. Retrieved from https://www.civilnet.am/en/news/669487/in-armenias-akunk-village-a-grassroots-push-for-solar-power/

- (2022). The economy of Artsakh: statistics, trends and losses. Retrieved from https://www.civilnet.am/news/661378/արցախի-տնտեսությունը․-վիճակագրություն-միտումներ-և-կորուստներ/

- Environmental Protection Committee of the Republic of Artsakh. Retrieved from http://mnp.nkr.am/օգտակար-հանածոներ/

- (2022). World Imagery Wayback. Retrieved from https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/wayback/

- (2022). Google Earth Pro software.

- (2020a). Hek of Shahumyan region: who are the owners?. Retrieved from https://hetq.am/hy/article/113430

- (2020b). Hydro-Power Plants in Artsakh’s Kashatagh Province: Former and Current Government Officials are Prime Shareholders. Retrieved from https://hetq.am/en/article/119594

- (2022). Azerbaijan violates ceasefire at night, throws mines in Khramort, Parukh-Khanapat villages. Retrieved from https://www.hetq.am/hy/article/142132

- Syunik 3. Retrieved from http://khorda.am/hy/hpp/սյունիք-3/

- Metagh Kaym Hydro Construction LLC. (2019). Kaytsaghbyur 1 SHPP, Republic of Artsakh, Lachin region. Retrieved from https://metaghkaym.com/en/project_item/kaytsaghbyur-1-phek

- am. (2014). RBC: Nagorno-Karabakh can be called the “Transcaucasian tiger.” Retrieved from https://www.panorama.am/ru/news/2014/07/19/melik-shakhnazarov/240578

- (2022). Planet. Retrieved from https://www.planet.com/

12.10.2022.

[1] This research was made possible by a grant from the USC Institute of Armenian Studies.