Putin and the 2022 Russian Military Conflict in Post-Soviet Lands

Coming to power after the break-up of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, Lukashenko had ruled Belarus in a highly autocratic fashion for almost three decades, while seeking to navigate his country within Moscow’s sphere of influence. However, the aging leader’s arbitrary rule began to teeter and he faced a major challenge in the election of 2020. When skewed and rigged election results were announced, hundreds of thousands of voters of Belarus peacefully protested their strong objections.

The West echoed moral support to the mass of citizens voicing democratic demands on the streets, but provided little material assistance. Somewhat optimistically and naively, the West trusted that the unarmed people would peacefully prevail over the coercive might of the internal and external dictators in Minsk and Moscow. Putin, by contrast, sensing a vulnerable and weakened regime, provided his fellow authoritarian colleague with external assistance to forcefully crush the peaceful demonstrators. With Moscow having successfully propped up the Lukashenko leadership, Belarus was pulled even more tightly into Putin’s orbit. It became once more, as in the Soviet era, a satellite of Moscow. Joint military manoeuvers in early 2022 seemingly sealed the political fate of Belarus. The Russian troops never left, ensuring a firmly pro-Moscow regime in Minsk. The Russian armed forces would also be used for an invasion of Ukraine.

For two decades, Putin had sought to reverse the Western drift of Kyiv, particularly the eastern extension of NATO, and demanded the demilitarization of Ukraine. He threatened war if the Zelensky government did not yield, but the youthful and previously untested Ukrainian leader stood firm, despite the hundreds of thousands of Russian troops assembled on the border. Putin, an aging, increasingly isolated, and angry totalitarian ruler, unleashed a military assault on the Ukrainian democratic state. With the twin goals of a coup and installing a compliant puppet regime, Moscow employed surgical air strikes and the landing of assassination squads, but the initial efforts failed.

Subsequently, Putin opted for a slower and more brutal three-pronged invasion campaign from the North, East and South. Increasingly the aggressive Russian battle plan targeted the Ukrainian civilian population with massive artillery and aerial bombardments, cutting off electricity, fuel and food. It is a war of aggression and involves war crimes against civilians. It even put at grave risk Europe’s largest nuclear power station and raised the nightmarish spectre of a continental environmental disaster. His bellicose threats of nuclear weapons escalation is chilling.

Putin’s initial territorial goals include expanding the strategic Crimean naval outpost of Sevastopol that dominates the northern shores of the Black Sea, re-asserting full military control over the Sea of Azov, and providing land bridges east to Russia and west to Transnistria, the breakaway Russian-dominated Moldovan state. In so doing, Putin seeks to reduce Ukraine to a landlocked and increasingly vulnerable regime. It seems his ‘real-politik’ aim is at least to bifurcate Ukraine into two halves, divided by the Dnipro/Dnieper River. In so doing, Putin would greatly expand upon his Donetsk and Luhansk puppet states. Ultimately, if he cannot control Ukraine or at least turn it into an unarmed, neutral buffer state, it seems he would prefer to make it a wasteland.

Echoing Stalin in the 1940s, Putin seems to have set his sights on establishing a new Russian bloc, ranging from Belarus in the North to the Crimea in the South. In a challenge and response international relations dynamic, NATO has been re-energized, re-unified and re-armed. Ironically, Putin has fostered a stronger and more determined adversary. There is a growing gulf and increasingly polarized military divide between the US-led NATO countries in the West and Moscow and its satellite states in the East. It seems like the beginning of a new Cold War, if we do not rapidly escalate into a hot war.

March 7, 2022

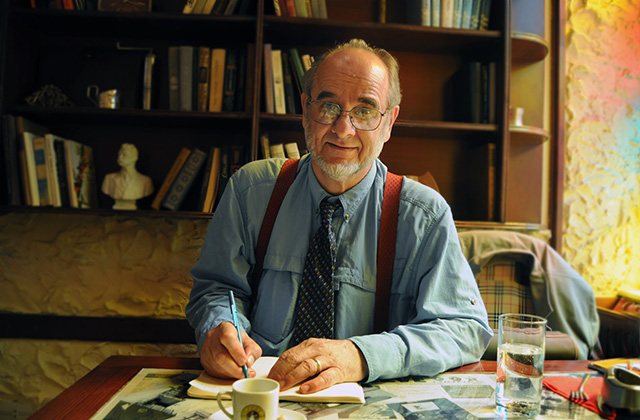

Alan Whitehorn is an emeritus professor of political science and writes on international relations and ethnic conflict.