War Crimes and Genocide in Ukraine

In recent years, April has often been described as the month of genocidal mourning for Armenians, Jews and Rwandans. Today we read the stark headlines and watch the horrific images of thousands of Ukrainian civilians killed by Russian armed forces in Moscow’s war of aggression against Kyiv. So many unarmed ordinary citizens targeted in Bucha, Mariupol and other cities. We agonize as to how and why such malevolent acts can occur in the 21st century.

How does one ‘think about the unthinkable?’ How does one ‘describe the indescribable?’ What overarching descriptive terms should we use? What can we do to help those suffering from such mass violence and severe trauma? So many of us feel overwhelmed. We are confronted by analytical and moral challenges in trying to understand war and genocide. Raphael Lemkin, the founder of the concept of genocide, observed that genocide occurred in history before the word was even created in the 1940s. The history of humans has been marked by episodes of great cruelty and mass killings, where groups that were perceived as different were targeted for persecution and slaughter. These violent and brutalizing acts often occurred during war.

While formulated at different times in history, the three legal terms — war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide — are interrelated and overlap. They constitute key foundational pillars in international law relating to mass atrocity crimes. War was the common feature in the emergence of all three concepts.

The concept of war crimes arose from the Hague conferences in Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These sessions sought to regulate the conduct of war in modern times, with its increasingly lethal weaponry. The 1907 Hague convention recognized the principle of the “laws of humanity” and the “laws and customs of war” that had been “established among civilized peoples”. Amongst the acts prohibited were: the deliberate harming of unarmed civilians, inhumane treatment, torture, compulsory slave labour, and willful killing of civilians.

The concept of ‘crimes against humanity’ emerged in 1915 during World War I, when the British, French and Tsarist Russian governments issued a formal joint international declaration that warned the ‘Young Turk’ government about the mass deportations and massacres of Armenians within the Ottoman Empire. Earlier massacres had occurred in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, despite repeated protests from European governments.

The concept of genocide emerged in a book by Raphael Lemkin during World War II, but its roots go back further. Following World War I, Lemkin, a Jewish university student in Poland wondered: Why were there domestic laws for the punishment of the murder of one person, but not international laws against mass murder by political leaders, such as the wartime Turkish military dictators?

A decade later in the 1930s, Lemkin proposed the precursor twin concepts of “barbarism” and “vandalism”. The former described harming and mass killing of civilians, while the latter the destruction of cultural property. During World War II, Lemkin formulated a synthesis of the two concepts with the creation of the new term ‘genocide’. This term first appeared in 1944 in a key book on the Nazi deportations and mass murder of Jews during the Holocaust.

In 1948, the United Nations passed the “International Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide” which included the following features: 1) killing members of a group; 2) causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of a group; 3) deliberately inflicting on a group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; 4) imposing measures intended to prevent births within a group; 5) forcibly transferring children of one group to another.

A group focus was central to the definition and four groups were specifically listed for protection: national, ethnic, religious and racial. Not all possible groups were listed by the UN Convention. In this regard, crimes against humanity is a more effective law to cover horrific crimes of mass killing and has generated more convictions. That said, in recent prosecutions at international tribunals and the International Criminal Court, the three terms – war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide – have tended to cluster together. They are important tools for punishing those guilty of past deeds and potentially deterring future genocidal war.

Psychologists try to understand the group dynamics of genocide in terms of three major roles: perpetrators, victims and bystanders. The perpetrators are the instigators and hostile aggressors. The victims are the vulnerable civilians, who are often a distinct ethnic, religious or racial minority. The bystanders are a large number, perhaps the largest, particularly in the context of a global society. Their role, therefore, is crucial.

The repeated Russian military bombardments on Ukrainian apartment buildings, schools and hospitals, targeting of large numbers of unarmed civilians, young and old alike, along with illegal imprisonment, torture and assassinations, all clearly fit the labels of war crimes and crimes against humanity. These brutal and barbaric acts are combined with Putin’s dictatorial declarations denying the democratic right of the Ukrainian nation to full sovereignty and freedom of national self-determination. Russian troops have followed this polemical imperialist and dehumanizing assertion by launching a massive foreign invasion and war of aggression against Ukraine. Notable too are the presence of at least three features of genocide: 1) mass killing; 2) causing serious bodily or mental harm; and 3) inflicting physical destruction on the conditions of life, in whole or in part. Russian war deeds clearly constitute genocidal acts. These overall malevolent features suggest a Russian government’s genocidal intent against the Ukrainian people. The Russian state and its armed forces are the main perpetrators. In as much as the Russian public supports these violent acts, they are complicit and are, in effect, accomplices. The governments and citizens of the outside world are for the most part bystanders. It is incumbent on them to decide how to respond to such crimes against humanity.

The bystanders are faced with several options: They might join in the scapegoating lies and attacks. Or perhaps too easily, they can continue to be largely indifferent. The reasons often posed for not caring include: it does not affect me directly; it is not my family or people; it is too far away, too distant. Or I am too busy and focused on something else. Or even, I am afraid to get involved, as I too might become a vulnerable target.

A third option is to stand up and try to stop the victimization. Somehow, we must resist the ‘sin of indifference’. The perpetrators need to be stopped by joint collective action. It is our shared global obligation to urgently protect the victims. The UN-inspired report Responsibility To Protect (RTP) laid out this important international conceptual foundation in 2001 and was formally approved by the UN General Assembly in 2005. Even a century ago, caring individuals, aid groups and sympathetic governments assisted orphan children of war and genocide, including my grandmother who had endured over a decade in refugee camps and orphanages. Today, we must reach out to help others who are in desperate need. It is our only hope to survive together on this precious planet.

April 16, 2022

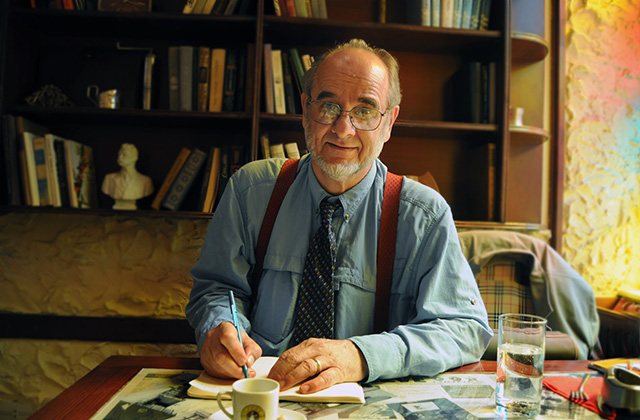

Alan Whitehorn is a professor emeritus at the Royal Military College of Canada and was a former JS Woodsworth Chair in Humanities at Simon Fraser University. Amongst his published books are The Armenian Genocide: The Essential Reference Guide and Just Poems: Reflections on the Armenian Genocide.