What you Need to Know about Peter Balakian, the New Pulitzer Prize-winning Poet

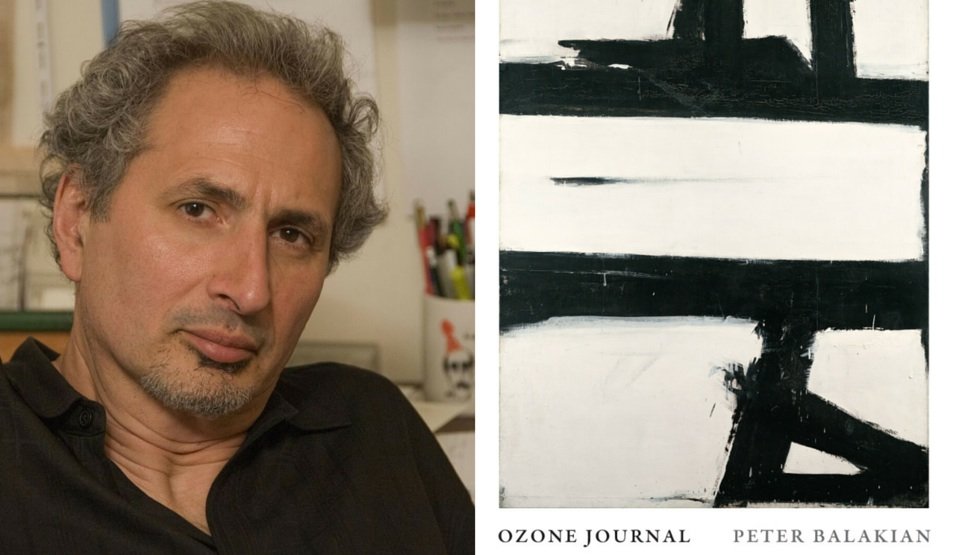

Peter Balakian, an English professor at Colgate University in Hamilton, N.Y., shot to the top of the poetry world on Monday when his new collection, “Ozone Journal,” won a Pulitzer Prize, The Washington Post reports. The judges praised his verse for bearing “witness to the old losses and tragedies that undergird a global age of danger and uncertainty.”

Balakian, 65, has published seven collections of poetry, but readers are more likely to know his nonfiction, particularly his writing on the Armenian genocide, such as “The Burning Tigris,” published in 2004. His memoir, “Black Dog of Fate,” was also widely praised.

“Prose books get public attention in a way that poems don’t,” Balakian said by phone from the University of Illinois, where he was giving a reading when he heard the good news. “But my productivity as a poet has been pretty continuous. My first book was in 1980. Poetry has been the center of my life from the start, even when I was writing in other genres.”

[Best poetry collections of 2015]

The centerpiece “Ozone Journal” is a 55-section poem set mostly in Manhattan in the 1980s when a young man is going through a crisis in his personal life and encountering his cousin who’s dying of AIDS. This set of events is reflected on by the persona’s older self in 2009 when he’s in Syria excavating the remains of his ancestors who were murdered during the Armenian genocide.

“I’m interested in the collage form,” Balakian said. “I’m exploring, pushing the form of poetry, pushing it to have more stakes and more openness to the complexity of contemporary experience.”

He describes poetry as living in “the speech-tongue-voice syntax of language’s music.” That, he says, gives the form unique power. “Any time you’re in the domain of the poem, you’re dealing with the most compressed and nuanced language that can be made. I believe that this affords us the possibility of going into a deeper place than any other literary art — deeper places of psychic, cultural and social reality.”

Those who know Balakian’s work are thrilled to see him get this new recognition.

Chris Bohjalian, whose 2012 novel, “The Sandcastle Girls,” was about the Armenian genocide, said, “Peter is one of the most gifted poets and memoirists and historians we have. I revere him as a writer and as an Armenian American, and I am so grateful for all he has done to raise awareness around the world of the Armenian genocide.”

Don Share, the editor of Poetry magazine, was surprised but pleased with the Pulitzer committee’s choice. “This book seemed slightly overlooked,” he said. “And yet Balakian has been a fine poet — and prose writer — for decades, so it feels very just.”

Share went on to describe the innovative nature of Balakian’s collection: “I think Americans are well used to seeing images of conflict in news stories — less so in poetry, which they expect to be lyrical. What’s so notable about Peter Balakian’s work is its argument that, as he put it recently in prose, ‘the poem that ingests violence also provides us with a form for memory that captures something of the traumatic event that has passed.’ In other words, his poems return the everyday human voice to those endlessly traumatic events that might otherwise have silenced it.”

Randolph Petilos, Balakian’s editor at the University of Chicago Press, said, “It’s interesting how sometimes people are known for their prose or novels, but in one sense, they’re sort of doing all that other stuff so that they can write poetry.” He cited Thomas Hardy and Victor Hugo as classic examples. “Hugo wrote in every genre that was available to him at the time, but he really wanted be known as a poet.”

What Petilos appreciates most about Balakian’s verse is that “he takes contemporary events and connects them to our ancient past in inventive and surprising ways.” He mentioned, in particular, the way Balakian recalls working in the World Trade Center in the 1980s to produce an elegy to those who died in the Sept. 11 attacks. “It’s just so immediate,” Petilos said. “It’s absolutely accessible. That’s probably why the Pulitzer committee picked this book.”

“Prizes are lovely affirmations from the jury of your peers, but I don’t think it changes anything in your writing,” said Balakian, who has won fellowships from the Guggenheim foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. “For me, I’m still at my desk pushing forward with my work. I’m working on a new book of poems right now, and I’m just excited to be able to keep writing and pushing forward. The main thing is to keep making good art.”

Here is a poem from Balakian’s Pulitzer Prize-winning collection, “Ozone Journal”:

Here and Now

The day comes in strips of yellow glass over trees.

When I tell you the day is a poem

I’m only talking to you and only the sky is listening.

The sky is listening; the sky is as hopeful

as I am walking into the pomegranate seeds

of the wind that whips up the seawall.

If you want the poem to take on everything,

walk into a hackberry tree,

then walk out beyond the seawall.

I’m not far from a room where Van Gogh

was a patient — his head on a pillow hearing

the mistral careen off the seawall,

hearing the fauvist leaves pelt

the sarcophagi. Here and now

the air of the tepidarium kissed my jaw

and pigeons ghosting in the blue loved me

for a second, before the wind

broke branches and guttered into the river.

What questions can I ask you?

How will the sky answer the wind?

The dawn isn’t heartbreaking.

The world isn’t full of love.

Reprinted with permission from “Ozone Journal” by Peter Balakian, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2015 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

By Ron Charles