Steve Jobs took the Armenian Genocide personally

On Friday, wrists around the world will welcome the most anticipated gadget since the iPad came to our fingertips five years ago. The Apple Watch has stirred breathless speculation, imitation, and excitement long before its reveal last September. But the date chosen for its release has caused a too-bizarre-to-be-true historic collision that Apple’s founder would likely never have allowed to happen, the Daily Beast writes.

One hundred years after Steve Jobs’s adoptive family escaped the Armenian Genocide, the company he created is releasing its biggest new product on the centennial of a mass killing that left 1.5 million dead at the hands of the Ottoman Empire.

And activists are worried that Apple’s latest masterpiece will distract an audience from an anniversary that they hope will finally force the Turkish government—which has long refused to call the slaughter a genocide—into accepting its bloody past.

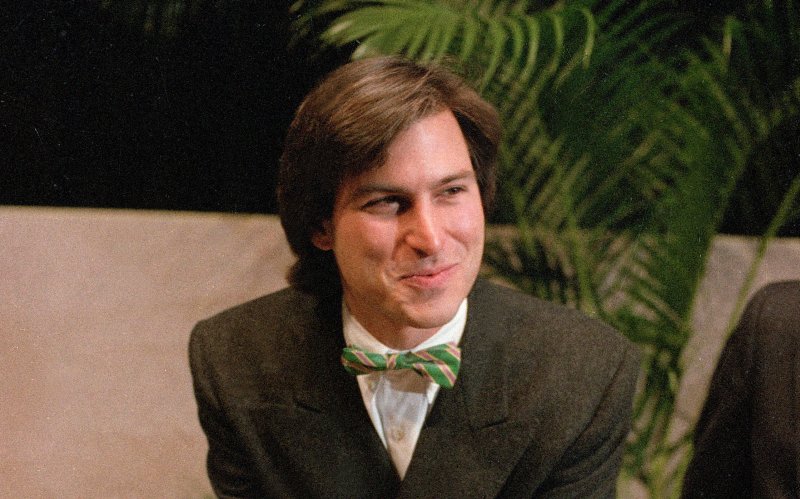

Steve Jobs’s birth parents weren’t Armenian, but he was raised in the shadow of that heritage by an adoptive mother whose family escaped the killings for safety in America in the 1910s. And Jobs, though he never spoke publicly about his ties, appeared to feel a deep connection with his family’s heritage and the historic bloodshed they experienced. He even spoke conversational Armenian.

In 1955, Clara Hagopian and Paul Jobs, a young couple who spent nearly a decade trying to have children of their own, adopted a Syrian-American baby and named him Steve. Steve Jobs never met his birth father and often spoke about the strong connection he shared with his adoptive family. “They were my parents 1,000 percent,” he told Walter Isaacson for his 2013 biography. “[My biological parents] were my sperm and egg bank. That’s not harsh, it’s just the way it was, a sperm bank thing, nothing more.”

Hagopian’s mother, Victoria Artinian, was born in the port city of Smyrna in the 1890s. Smyrna, an ancient biblical town and possible birthplace of Homer, had enjoyed relative calm until the early 1920s. Filled with diplomats and citizens of high social ranking, the world was shocked when, in 1922, the city was pillaged and burned to the ground. Images of fiery deaths and charred buildings were seared into the historical imagination. Ernest Hemingway’s “In Our Time,” which was written three years later, begins with an ode to the fated town: “The strange thing was, he said, how they screamed every night at midnight. I do not know why they screamed at that time.”

Artinian arrived in the United States on the Greek boat Megali Hellas in 1919, and soon after met Louis Hagopian. He had made the same trip seven years earlier, lucky to escape his hometown of Malatya. Mass murders began there in the late 1800s and a few years after Hagopian came to America, nearly the entire population of 20,000 Armenians living in Malatya was wiped out.

“Anybody with family coming from those two places would have been really branded by the genocide,” says Peter Balakian, a humanities and English professor at Colgate University and author of two books on the Armenian Genocide.

As the newlyweds settled down briefly in Newark, New Jersey, tens of thousands of genocide survivors were fleeing the killings and making their way to the United States. A web of Armenian refugees had begun to spread out across the world. They settled in major cities, from Aleppo to Newark, which is where Victoria and Louis Hagopian had a daughter named Clara in 1924.

A few years later the family moved to California. According to the 1930 U.S. Census, Clara was raised by her mother and elderly grandmother in San Francisco, where she met and married Paul Jobs, a freshly decommissioned Coast Guard mechanic, in 1946.

The Armenian refugees were, for the most part, welcomed by Americans, many of whom felt a shared Christian identity with the refugees and were impressed by the newcomers’ entrepreneurial spirit. Indeed, the refugee cause was the most famous of its time.

“It’s the largest NGO relief movement in U.S. history,” Balakian says. “The Armenians were really a celebrated minority group.” Scholars estimate that the American Committee for Relief in the Near East raised the equivalent of $1.5 billion to assist the new refugees. A film about the genocide released at the time grossed a whopping $2 billion in today’s currency.

Future president Herbert Hoover was put in charge of relief efforts for Europe, and was particularly passionate about the Armenians’ plight. “Probably Armenia was known to the school child in 1919 only a little less than England,” Hoover wrote in his memoirs.

Not so much today. When Apple announced it would release its newest product on April 24, leaders of the Armenian community were taken by surprise. It seemed that the watch, which has spurred years of breathless speculation, could easily overshadow news of the genocide commemoration events. Apple did not respond to request for comment for this article.

Jobs was viciously private and didn’t make public his ancestry or engage in the genocide classification debate that Turkey continues to dig its heels into. The Armenian church in Cupertino said that despite multiple invitations, Jobs never got in touch with the area’s expat community. But Jobs’s feelings about the killings became apparent on a tense standoff during a luxurious Turkish vacation, according to the tour guide who led the visit, and who later blogged about the incident.

In 2007, Jobs and his family traveled around Turkey on a private yacht tour and spent 10 days visiting the country’s sites with guide Asil Tuncer. It went smoothly until the last day, Tuncer told The Daily Beast, when the group visited the Hagia Sophia. Once a Byzantine church, it was later converted into a mosque during the Ottoman Empire, and is now one of Istanbul’s must-see tourist destinations.

“What happened to all those Christians, suddenly gone like that?” Tuncer recalls Jobs asking him as they gazed at the minarets. Then, he reframed the question: “You, Muslims, what did you do to so many Christians? You subjected 1.5 million Armenians to genocide. Tell us, how did it happen?”

Tuncer says he felt trapped, unsure whether to answer with his opinion or evade an argument in the polite manner he was trained to use as a guide.

“To expect from a Turkish guide to accept that [question], even if true, it’s not very good. For example, it’s like if I come to U.S. and ask, ‘Tell me how, you killed the Indians?’” But he says Jobs insisted he respond.

“First I said, ‘Sir, maybe these are not good things to talk on Istanbul tour. Let’s have fun—this is your real purpose, to learn about the buildings and history.’ He said, ‘No, no, no, I want to hear your answer.’”

“I said, ‘People kill each other, of course, this is a war, but it is not deliberately genocide,’” he says he told Jobs. “Then I tried to be nice. So I did my best.”

Tuncer says Jobs’s face fell, and he looked “miserable.” Earlier in the trip Tuncer says Jobs had described Apple’s vision for a tablet and showed him the new laptops. But now his previously amiable demeanor had changed.

Jobs cut the day short, deciding to return to the boat docked in Istanbul’s port, and not finish out the last day of the visit. “He was not happy with my answer, and maybe he didn’t feel very good after. I can’t exactly say. He didn’t tell me. He just said, ‘I want to go back to port.’” (Jobs’s family has not publicly responded to Tuncer’s account of the tour.)

Tuncer, who now works for a tour company called Legendary Journeys, says the goodbye was chilly when he put the Jobs family on their plane home. “This person coming from the diaspora, I don’t expect he will say, ‘Oh, yes, you are right, I am wrong,’” he says. “He was disappointed in my answer.”

“He didn’t have Armenian blood himself, but because of his mother, he felt a great pull and affinity toward the fact she was, for all intents and purposes, a genocide survivor,” says Phil Walotsky, the spokesman for the Armenian Genocide Centennial Committee of America.

The Apple Watch release has rattled those who’ve spent months planning for a commemoration they hope will finally bring about recognition of the widespread killings by the Turkish government, which has suppressed its ghost against a flood of international condemnation.

“Do we think Apple did this intentionally? Of course not,” says Walotsky. “If Steve was still around or if this was brought to their attention earlier—I’m sure there were folks in leadership who knew about Steve’s background—would they have picked April 24? Probably not.”

But he doesn’t blame Apple for the date overlap. The anniversary date doesn’t carry the same weight as other dates do, and hasn’t sparked any outcry as if the watch was being released on, say, Holocaust Remembrance Day. “It doesn’t have the same stickiness in the American psyche as other dates do,” says Walotsky.

Not everyone feels so benevolent. Benjamin Abtan, president of the European Grassroots Antiracist Movement, is organizing a weekend of events to commemorate the anniversary. “It cannot be by chance,” he says of the Apple Watch release date. “It doesn’t mean there as an intention to overshadow the Armenian Genocide, but for all people who know even a little about the Armenian Genocide, they know it’s a very big day that everybody’s been expecting for a long time. The date is very symbolic of this trauma.”

Abtan doesn’t expect the watch’s release to push out news of his efforts to get the Turkish government to recognize the genocide, but he’s already been disappointed by the American media’s coverage of the tragedy.

Still, Walotsky says he considers it lucky that Apple decided not to release the watch with its typical line-around-the-block shopping frenzy. “In terms of being the second story that day, at least that gives us a chance of having a little equal footing in terms of being able to educate people about this and ensure the mainstream media is reporting on this,” he says.

Walotsky hopes that tomorrow, Apple will make an effort to pay tribute to its founder’s heritage and the strangely aligned anniversary. With Tim Cook’s advocacy around LGBT issues, and Apple’s environmentally conscious campaigns, he says it’s not difficult to imagine the image-conscious company paying tribute.

“Maybe in a strange way the launch of the watch brings more attention to the anniversary,” he says.