100 Lives Stories: Manuschak Karnusian

“There comes a point when you realize that more than just a language has been lost.

Manuschak Karnusian was born in 1960 to a Swiss mother and an Armenian father. She grew up in Gstaad, Switzerland, and pursued a career as a bookseller and a flight attendant with Swissair before becoming a trainee journalist with the Berner Zeitung newspaper. She worked as a journalist and editor for the Förderband radio station and the newspaper Tessiner Zeitung. Manuschak and her partner Jürg Steiner ran a press office in the Swiss canton of Ticino and co-authored two travel guides for the area. Today, Manuschak Karnusian is the head of communications at the Swiss organization “Brot für alle” (“Bread for Everyone”). She lives with her partner and their two children in the vicinity of Bern.

“For a long time I distanced myself from my Armenian identity. My father, James Karnusian, was very committed to the Armenian cause and the Genocide was a recurring topic of conversations in our home. As a child and adolescent, I didn’t want to associate my own identity with such an atrocious crime – the tragic history of Armenians was too much of a burden for me to carry,” says Manuschak Karnusian, who has published a book on Armenians in Switzerland titled “Unsere Wurzeln, unser Leben” (“Our Roots, Our Life”).

Her father, James Karnusian, was co-founder of the Switzerland-Armenia Association in Bern and worked tirelessly to raise public awareness about the Genocide that was being committed against the Armenian people. He wrote books, made films and established the Pan-Armenian World Congress.

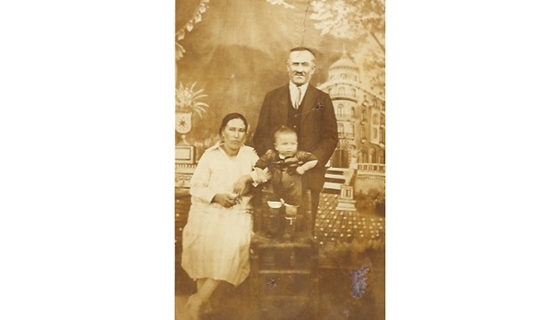

His parents, Lucie Gostonian and Sarkis Karnusian, had survived the Genocide of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. His mother was born in the Cilician town of Marash (now Kahramanmarash, in southern Turkey) in 1900. When she turned 15, the large-scale deportations and massacres had already begun. All 33 members of her family were murdered in cold blood. She was the only one to survive, found injured by a Muslim who took her to doctor Jakob Künzler in the city of Urfa (now Sanliurfa, in southern Turkey).

A citizen of politically-neutral Switzerland, Künzler was allowed to stay in the Ottoman Empire during the war and was often the only person able to provide medical care to injured Armenians in and around Urfa. In 1914-1918, Jakob Künzler and his wife Elizabeth Bender managed to save many Armenians from imminent death.

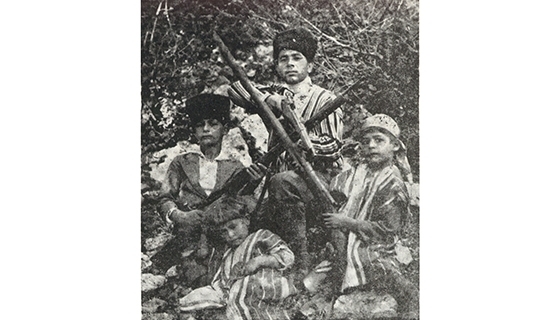

When the American Committee of Near East Relief, which was taking care of tens of Armenian orphanages in and outside the Ottoman Empire, decided to move Armenian orphans out of Turkey in 1922, Jakob Künzler procured safe passage for 8,000 orphans from southern and eastern regions of Turkey to Syria and Lebanon. Among them was Lucie Gostonian. Manuschak Karnusian assumes that this is how her grandmother came to Aleppo in Syria, where she met her future husband, Sarkis Karnusian, at a refugee camp. Sarkis Karnusian was one of the resistance fighters who had courageously defended the villages in the vicinity of Musa Dagh. The couple had five children and raised them all in the Lebanese capital of Beirut.

Manuschak Karnusian was born in Switzerland and neither she nor her siblings had much contact with their father’s relatives in Beirut. “My Armenian grandfather died in the 1950s, before I was born. I met my grandmother maybe three times in my life, but I couldn’t speak with her. I didn’t speak Armenian and she didn’t speak English,” Manuschak Karnusian recollects. In the 1970s, her grandmother and one of her uncles immigrated to Toronto, where Manuschak visited them once. “Mezmama invited me to lunch and made me bulgur. She shared an apartment in a large building with my uncle. When she took the bulgur out of the cupboard I saw that it was teeming with bugs. My grandmother und uncle, so it seemed to me, led a life of poverty in a run-down place.”

Years passed, and yet “my roots wouldn’t be brushed aside,” says Manuschak.

“It was in particular my father’s death that made me feel as if I had been cut off from my roots. I realized that I hardly knew my own family’s history because my father wouldn’t talk much about his parents’ story. Maybe he didn’t know much more himself, and we didn’t ask further questions.”

Manuschak Karnusian began reaching out to Armenians in Switzerland. She wanted to find out whether other Armenians knew their families’ stories better and how they defined their identity. This gave the journalist the idea to write a book about it. “I wanted to show what Armenians are like, how they live their culture, and how they deal with the tragic history of their people. It was my intention to take a look at Armenian life beyond the Genocide. I wished to point out that these people are alive, that they are here, that they are happy – that they should not only be seen in the narrow context of the Genocide.”

She says that she mulled over the idea of writing about this topic for a while because she was not sure that she would be able to find the time and money necessary to bring it to fruition. One day she received a letter from Toronto, to her great surprise. “The day I decided to write this book I received a letter informing me that my siblings and I had inherited some money from our uncle. I took it as a sign. Thanks to the inheritance, I was able to partly finance the book. It gave me some extra courage.”

In order to pay for the remainder of the price for publishing her book, she launched a crowdfunding campaign. This is how the book about Armenians in Switzerland became an entirely independent production. “I wrote down 12 life stories. Each of them is accompanied by explanatory text on history, culture, politics and economics. The texts shed light on Armenia’s past, providing information on the role of the church, the importance of the language, the solidarity of Switzerland with Armenians. It led me to ask a series of questions:

‘What is Armenian identity? What is its essence? Why do people who have been living here for four generations and no longer have anything to do with Armenian history still feel Armenian?’

I set out to find the reasons.”

One question, however, remained unanswered: “Why my father hadn’t taught us Armenian, that’s what I wondered about most after his death. Back in the days, everyone said that he had to learn German and didn’t speak Armenian because of that. As children, we were content with this answer. After all, he had gone to an English Baptist seminar not far from Zurich to pursue his theological studies. When he took up his first pastoral post after ordination, he had to learn German. It all seemed logical to us children at the time. But later, when he was no longer with us, I thought to myself, ‘That can’t be it.’ There comes a point when you realize that more than just a language has been lost. The language is the key to the culture. Why he didn’t give us this key, he, who was so committed? That’s a question I haven’t been able to answer satisfactorily to this very day.”

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.

Cover photo: Stefan Anderegg/Bernerzeitung